0105: D Snippets I - Observer vs. Singleton

When it comes to building a UI, it isn’t always about the Widgets. Often, you need to find ways to handle Widgets in non-Widget-y ways just to keep things manageable.

For instance, over the last year, I’ve touched on a few design patterns—sometimes, quite sloppily—while incorporating such things as OS detection, accelerator keymaps, fonts, and groups of Widgets such as Radio- or ToggleButtons.

So, we’ll start off with a couple of more strictly-built (read: adhering more to the strict definitions) design patterns and, over the next while, we’ll go over other bits of D-specific code that will help in various ways when building a UI. So, without further ado, let’s dig in…

Singleton vs. Observer

First, what’s the difference between the two?

The Singleton assures us that we have one instance of a class object. And no matter how many times we create more instances of that class in our code, we’re always dealing with a single instantiation.

The Observer allows a single object to inform several other objects of its internal changes.

In both cases, we’re talking about a one-to-many relationship. So, that’s not the difference.

The Observer pattern is named for the object that needs to know what’s going on elsewhere. The Singleton is that elsewhere and so we might infer that both are actually part of the same pattern… and I’m not saying they can’t be, but there must be a reason they both exist, so let’s step back and look again…

The definition of the Observer pattern—a single object keeps others informed of internal changes—gives us a clue. The observed object is dynamic. It changes over the lifetime of the application.

And the Singleton? Use cases cited by experts speak of resources—a print spooler, a window manager, a font list, or other OS-specific stuff. In other words, things we expect to remain static during the application’s lifetime.

So, a Singleton is used for a static resource and Observers keep an eye on a dynamic resource.

The rest of this post will first present the general specs for a Singleton in D, then look at a working example.

The Singleton – a Generic Example

Note: There is no UI for this example. You’ll have to run it in a terminal.

Here’s what the DSingleton preamble looks like:

class DSingleton

{

private:

// Cache instantiation flag in thread-local bool

static bool instantiated_;

// Thread global

__gshared DSingleton instance_;

These two properties work together to make the Singleton thread-safe. In essence, they allow us to work with the Singleton whether we’re working with a application having a single thread or multiple threads.

Next, the constructor…

this() {}

In other words, we don’t have a constructor. Not really. Note also that the constructor definition is in the part of the class marked private which means no outsider can call it. Why? Because that way, no one can call it by accident. And why don’t we want anyone to call it? Because we don’t instantiate the DSingleton with a constructor call. We use this instead:

static DSingleton get()

{

if(!instantiated_)

{

synchronized(DSingleton.classinfo)

{

if(!instance_)

{

instance_ = new DSingleton();

write("Creating the singleton and");

}

instantiated_ = true;

}

}

else

{

write("Singleton already exists, so just");

}

writeln(" returning an instance.");

return(instance_);

} // get()

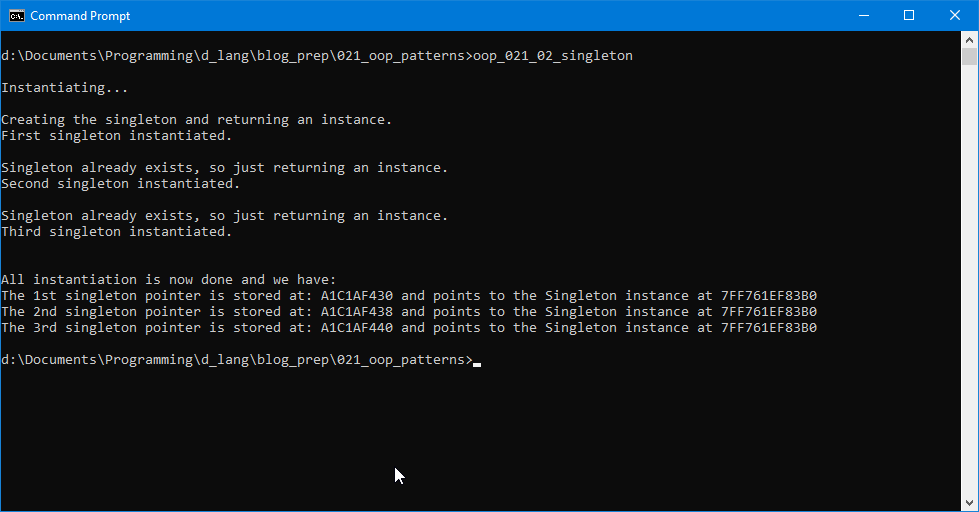

All those writeln() calls are there just as proof that the system works, BTW.

Wherever your code needs access to the Singleton, you start by calling get(). There’s a bit of D-language hocus pocus going on here and I won’t pretend to know exactly what it does (it’s above my pay grade). In a nutshell, though, this function checks to see if an instance of the Singleton exists either locally (in the current thread) or globally (in any possible thread) before deciding whether or not to create one.

The Getter Function

This just helps to prove that this is, indeed, a Singleton:

DSingleton* getInstance()

{

writeln("the Singleton instance at ", &instance_);

return(&instance_);

} // getInstance()

It spits out the address of the pointer to the Singleton as well as the address of the Singleton itself so we know that, even though we have three pointers, they all point to the same instance of our DSingleton.

The Singleton at Work

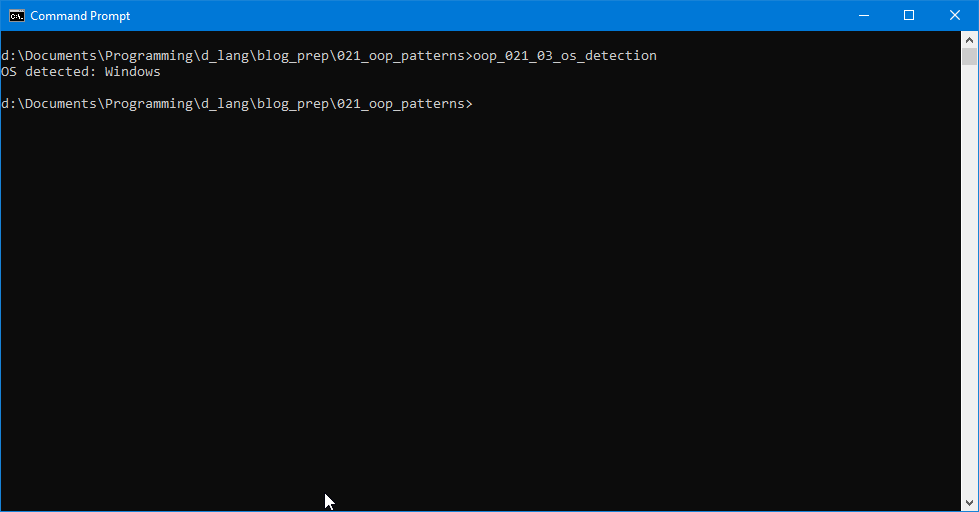

Note: As with the last example, there is no UI for this. You’ll have to run it in a terminal.

Detecting the user’s OS—something that’s not expected to change while the application is running—is a perfect example of Singleton use.

How we get from the generic example to this specific one comes down to this:

- add a string property to store the OS type,

- supply code to the constructor that does the detection and store the results, and

- replace

getInstance()with something more appropriate likegetOS().

It’s also a good idea to rename the Singleton to reflect what we’re dealing with and that means editing all those places in the code where we refer to it by name.

In this case, we:

- change the name from

DSingletontoS_DetectedOS(the ‘S’ indicates Singleton), editing all references throughout the code, and - add the property string

_os_type.

The constructor becomes:

this()

{

version(Windows)

{

_os_type = "Windows";

}

else version(OSX)

{

_os_type = "OSX";

}

else version(Posix)

{

_os_type = "Posix";

}

} // this()

Our replacement getter looks like this:

string getOS()

{

return(_os_type);

} // getOS()

Conclusion

Next time, we’ll start by taking a closer look at the Observer.

Until then, happy coding.

Comments? Questions? Observations?

Did we miss a tidbit of information that would make this post even more informative? Let's talk about it in the comments.

- come on over to the D Language Forum and look for one of the gtkDcoding announcement posts,

- drop by the GtkD Forum,

- follow the link below to email me, or

- go to the gtkDcoding Facebook page.

You can also subscribe via RSS so you won't miss anything. Thank you very much for dropping by.

© Copyright 2024 Ron Tarrant